The Research Animals That Have Made A Difference

- Jan 8, 2019

- 5 min read

Over the last 40 years, every Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine but one has depended on work using animals. From modern vaccines that protect us against polio, TB and meningitis, to the development of Tamoxifen that has led to a 30% fall in death rates from breast cancer, the role of research animals cannot be underestimated.

In a recent post Understanding Animal Research pointed out the major milestones which have ensured the UK has some of the best laboratory animal welfare conditions in the world. Animal research is one of the most heavily regulated industries in Europe. The EU directive on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes is internationally recognised as offering an excellent level of protection for laboratory animals. The directive was adopted to keep up with science and make sure that best methods and in particular the 3Rs are applied as soon as they are available. The EU directive regulation harmonises European animal laboratory standards, improving animal welfare across the EU.

On World Day for Laboratory Animals (WDAIL), we count down the top five research animals in the last century.

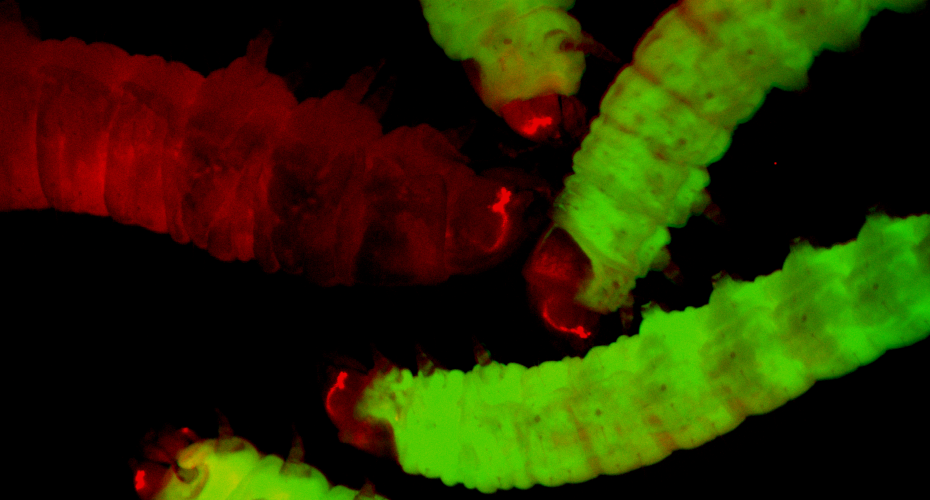

Drosophila melanogaster

The Drosophila, more commonly known as the common fruit fly, has played a crucial role in advancing genetics and developmental biology. The Drosophila was first famously used by Thomas Hunt Morgan, who demonstrated that genetic information is carried on chromosomes and went on to win the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1933.

Drosophila is a popular and successful research animal; while their brains are relatively simple, their nerves and muscles are highly developed. In more recent research, Drosophila has been used to understand the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases, with our knowledge of diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s rapidly expanding in the last few decades. Alzheimer’s Society says:

“Tau is the name of a protein that is usually found in the longest part of our nerve cells, called the axon. This protein plays an important role in maintaining the structural health of brain cells as well as their ability to communicate with each other… Fruit fly models have shed significant light on what appears to be happening in the human brain when people develop Alzheimer’s disease. When tau becomes abnormally hyper-phosphorylated it disrupts the communication between cells.”

Genetically Modified (GM) Mouse

For the last 13 years, the GM mouse has been the go to animal model for research. They represent 61% of the total number of animals used for scientific purposes. Since a mouse strain was sequenced and analysed, GM mice have transformed medical research.

Researchers are able to manipulate mice genes so they develop diseases that don’t naturally affect them, not to mention they have similar reproductive and nervous systems to humans and naturally suffer from the same debilitating diseases such as cancer and diabetes. Human diseases can be studied with great accuracy as 80% of human and mice genes are the same, and a further 10% are very similar.

They’re used for a wide range of research, playing a crucial role in fundamental research. From heart disease to cancer, GM mice have been at the forefront of biomedical breakthroughs and are constantly making headlines. In 2015 alone, mice were crucial to the following breakthroughs:

Zebrafish

The zebrafish has been an important model of human disease as their genetic structure is remarkably similar to ours. Researchers have found the equivalents of many human diseases in the zebrafish. After mice and rats, fish are the third most commonly used protected species in research.

Zebrafish which develop leukaemia has allowed researchers to screen their genes for mutations that contribute to the disease and to test anti-cancer agents. With transparent embryos, zebrafish give researchers an excellent opportunity to study its beating heart. Just a few years ago, the British Heart Foundation launched their ‘mending broken hearts’ https://www.bhf.org.uk/get-involved/mending-broken-hearts/research/zebrafish—do-they-hold-the-secret-cure campaign to study the zebrafish’s remarkable ability to regenerate their damaged hearts.

Dr Tim Chico a consultant cardiologist at the University of Sheffield and also studies zebrafish said:

“We can switch off genes and see how the zebrafish regrows blood vessels to repair damage. If we could switch the right genes on in humans then we could live longer and survive better after a heart attack.”

Non-Human Primates (NHP)

There’s a great deal of controversy in using NHP in research, as they’re our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. But, it’s this very reason why they are such valuable research animals. NHP can be the best model for understanding human disease and finding a way to treat and eradicate it due to their high degree of genetic, anatomical and physiological conservation.

In the last year alone NHPs have contributed enormously to biomedical research, pioneering breakthroughs to vaccinate and treat both Ebola and HIV. In an earlier post, EARA spoke to the president of Mapp Biopharmaceutical, who pioneered the experimental drug Zmapp. He said:

“We tested on macaques as it’s believed to be the model most representative of the course of human disease for filoviruses like Ebola.”

ZMapp has treated two American aid workers under the ‘compassionate-use’ doctrine. More is being made, and after promising results in NHP the drug will soon undergo human trials.

More recently, researchers were able to try a radical new approach to vaccinating against HIV. Researchers at the Scripps Research Institute in California altered the DNA of NHPs, introducing a new section of DNA that has instructions to neutralise HIV. The vaccination was able to protect NHPs from all types of HIV for at least 34 weeks.

These advances would simply not have been possible without research using NHPs. It’s however important to note that NHPs are not widely used in medical research. In fact, they make up 0.1% of research animals.

Dogs

Research using dogs has also remained controversial. While they make up 0.25% of the total number of animals used in 2011 in the EU, dogs have played a pivotal role in biomedical research. The Nobel Prize-winning discovery of insulin in 1923 would not have been possible without research on dogs. This medical breakthrough has made diabetes a manageable disease. Diabetes UK state on their website:

“Knowledge gained from animal research has been significant and essential in numerous diabetes breakthroughs, for example, the use of insulin and islet cell transplantation would not be available if it had not been for animal research.”

More recently, dogs have been crucial for research into new heart medicines. Research into pacemakers supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation and performed by Maastricht University requires the use of dogs because their hearts are a similar size to ours and because their ‘electrical wiring’ behaves much like ours. Though both organisations came under fire by animal rights activists, dogs are especially suitable for cardiovascular studies due to the resemblance in heart connectivity and size to the human heart. Previous research on dogs led to the development of blood transfusion procedures and the creation of the electrical defibrillator to restore normal heart rhythm.

World Day for Laboratory Animals

WDAIL was established by the British National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS). The day is usually marked by protests and demonstration by animal rights activist to highlight ‘the suffering of animals in experiments.’

More recently, researchers and others from the science community have begun to challenge the narrative of WDAIL. Speaking of Research has called for researchers to stand up for science and for public interests in advancing scientific understanding and medical progress. We at EARA agree.

On WDAIL, what research animals do you think has made the biggest difference in biomedical research?

#PressRelease #AnimalResearch #Mice #Dogs #Dogs #ZebraFish ##Monkey